Stephen Lungu clutched his bag of petrol bombs tightly as he and his fellow gang members approached the large gathering inside the tent. It was just before 7 PM and a huge crowd had gathered to hear the Gospel in Machipisa township on the outskirts of Harare, capital of Zimbabwe. Stephen was the leader of a detachment of a dozen teenage thugs from the Black Shadows, a gang intent on stirring up trouble and rebellion against the white government of pre-independence Zimbabwe. And their intent on this particular evening in 1962 was to blow up the evangelistic meeting. “I want everyone inside that tent to die,” Stephen admonished his gang friends. “At 7 PM I will whistle and everybody throw their stones and petrol bombs into the tent entrance” (74).

With a few minutes to spare before the stroke of 7, however, Stephen stepped into the tent to listen. Now in his late teens, he was an angry and lonely young man, abandoned at the age of seven by his mother and left to fend for himself on the streets of Harare. His father had long since married another woman and moved to Malawi and he had lost contact with his younger brother and sister. He was illiterate, having had only four months of formal education and spending his younger years sleeping under a bridge, retrieving balls at golf and tennis clubs for a few pennies of income and scavenging food out of trash cans in the affluent white folks’ neighborhoods.

His anger and hatred had lately been fanned and given focus by his involvement in the Nationalist Youth League, which promoted a Marxist understanding of African history and advocated the violent overthrow of the minority white government of Rhodesia (as Zimbabwe was called then). Stephen and the Black Shadows aimed to contribute to their country’s liberation from white rule by stealing from whites and seeking to sow general chaos through thuggery and instigating riots.

While Stephen’s fellow gang members grew restless as 7 PM came and went, he continued to listen, first to a beautiful young girl from Soweto in South Africa telling of how Jesus had “transformed everything. There was a strange uncanny authority and resonance with which she spoke of forgiveness and a new start in life,” said Stephen, “and I suddenly felt very dirty and shabby” (75).

Then a Zambian preacher got up and spoke from Romans 6:23 about the wages of sin being death. These words rang in Stephen’s head as he reflected on all the hatred he felt towards so many people that had caused him to pursue a life of violence and chaos. When the preacher then quoted “2 Corinthians 8:9 – ‘For you know the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, that though he was rich, yet for your sakes he became poor, so that you through his poverty might become rich.’ Suddenly I began to understand what Christianity was all about,” said Stephen. “It was for someone like me! I could identify with this Jesus. He had suffered in all the ways that I knew so well. Poverty, oppression, hunger, thirst, loneliness. I had known all of these, and so had he… My wages were death, but Jesus paid the price for me. On the cross he had become a nobody that I could become a somebody” (80-81).

Still clutching his petrol bombs, Stephen stumbled forward to where the preacher was speaking, even though it was still in the middle of his message. Ushers tried to escort him away, but the preacher forbade them, continuing with his sermon.

A few moments later, rocks pelted the tent and petrol bombs went off, causing a stampede out into the surrounding fields. Stephen’s cronies had gone ahead with their violent plan without him. But the preacher remained, with Stephen on his knees in front of him, pouring out through tears of anguish his story of abandonment and heartache, of anger and violence.

Through the providence of God, the preacher himself had come to Christ and found healing after having been abandoned as a baby by his mother, and shared with Stephen Psalm 27:10: “Though my father and my mother forsake me, the Lord will take me up.” After hearing this, Stephen prayed, “God, I have nothing. I am nothing. I can’t read. I can’t write. My parents don’t want me. Take me up, God, take me up. I’m sorry for the bad things I’ve done. Jesus, forgive me, and take me now” (87).

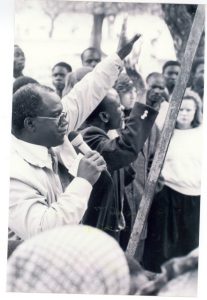

Stephen went back to his usual bridge to sleep under that night, but as an entirely new person. When he awoke and cleaned himself up, his career as a powerful evangelist got underway as he boarded a bus into the city and began preaching to the other passengers about what had happened to him the previous night. He was thrown off the first bus he tried this on, but when he exited the second one, a small crowd of seven people had been touched by his testimony and wanted to give their lives to Christ.

Stephen realised he didn’t quite know what to do, so he knelt down on the sidewalk with them and prayed, “God, I’ve met these good people on the bus just now, and I told them about how I found your Son Jesus last night. They’ve said they would like to meet him too, because I’ve told them how he loves everyone in the whole world. So, here they are.” Tears rolled down the faces of these new converts as they gave themselves to their Savior. More than forty years later, says Stephen, “I was still in touch with three of them – they became ministers of local churches” (99).

Besides telling people about Jesus, Stephen also felt he must turn himself in to the police and confess his crimes. “The love of Jesus arrested me last night,” Stephen told one of the senior policemen. “Last night I  became a Christian, and I realised that what I have been doing is wrong” (100). The incredulous policeman listened to Stephen’s story and tried to plumb him for information on his gang. Stephen confessed to everything he had done, but sought not to betray his old friends. Finally, the policeman said, “Well, Stephen, if your Jesus has forgiven you, we forgive you also. There is nothing to be gained from keeping you here. You are free to go.” Another policeman held out his hand and said, “Here is some money – go and buy yourself a Bible” (103).

became a Christian, and I realised that what I have been doing is wrong” (100). The incredulous policeman listened to Stephen’s story and tried to plumb him for information on his gang. Stephen confessed to everything he had done, but sought not to betray his old friends. Finally, the policeman said, “Well, Stephen, if your Jesus has forgiven you, we forgive you also. There is nothing to be gained from keeping you here. You are free to go.” Another policeman held out his hand and said, “Here is some money – go and buy yourself a Bible” (103).

Though he did not yet know how to read, Stephen went out and proudly bought himself a nice hardcover Bible, which he treasured. With it under his arm, he went out every day on the bus to preach in the central market, telling everyone he possibly could about Jesus. His old friends from the Black Shadows gang found out about this and would come and heckle him, calling him “Bishop” or “Vicar” and kneeling down and pretending to cry in the street. One of them even pulled a knife on him. Stephen also sought out a church to attend, but found that the parishioners there weren’t very enthusiastic about his preaching every day out in the marketplace – it wasn’t “respectable” – and his bringing mostly shabby new converts into the congregation.

Word had got back, though, to the Dorothea Mission, the South Africa-based Christian organisation in whose tent crusade Stephen had just come to Christ. One day as he was preaching, a man named Hannes Joubert, a Dorothea missionary from South Africa who had just moved to Zimbabwe, approached Stephen with an offer to join a Bible school which Joubert was starting in Harare. Stephen was the first student and was amazed at Joubert’s faith in starting this new venture. For he “had no money. He had no building. He had no teachers. He had few books. He had only one student – an uncivilized twenty-year-old straight off the streets whose knowledge of Christianity came from Marxist-driven ideology, one evangelistic tent service attended with the aim of petrol bombing it, and a few follow-up meetings afterwards” (124).

Furthermore, Stephen spoke little English, could not read or write and hardly knew how to eat with a knife and fork or to take a bath without spilling most of the water out of the tub. Stephen took up residence in Joubert’s garage, as it was against the law at that time in Zimbabwe for a black person to stay in a white person’s home, but this new home was an enormous improvement over his former one under the bridge.

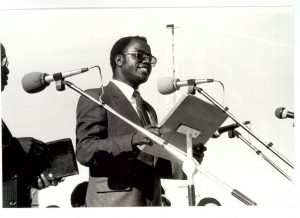

Stephen spent a number of years studying – learning to read and write, learning English, learning about the Bible and even learning about eating properly with a knife and fork! By the mid-1960s the Dorothea Mission welcomed him aboard as one of their missionaries and he began to go out preaching in the ensuing years on missions throughout Zimbabwe and in Mozambique, Malawi, Zambia, Botswana and South Africa. This was a time of major social and political upheaval in most African countries, as they gained independence from colonial powers or, in the case of Zimbabwe, continued to resist the oppression of the ruling white government.

Stephen spent a number of years studying – learning to read and write, learning English, learning about the Bible and even learning about eating properly with a knife and fork! By the mid-1960s the Dorothea Mission welcomed him aboard as one of their missionaries and he began to go out preaching in the ensuing years on missions throughout Zimbabwe and in Mozambique, Malawi, Zambia, Botswana and South Africa. This was a time of major social and political upheaval in most African countries, as they gained independence from colonial powers or, in the case of Zimbabwe, continued to resist the oppression of the ruling white government.

Reprieve for Zimbabwe did not come, however, until 1980 and for South Africa not until 1994. But it meant that Stephen and his colleagues were preaching the message of what many Africans considered “white man’s religion”. Many evangelistic rallies would invite violent protests and find the Dorothea missioners fleeing in a hail of rocks and bricks, or being beaten by a mob. Stephen and others were once kidnapped at 1 AM by members of the Malawi Congress Party Youth League, who were upset that a Dorothea mission in Blantyre had attracted more people than their political rally. Intense prayer by many others secured their release.

New impetus came into the ministry of the Dorothea Mission with the arrival from England in the mid-1960s of Patrick Johnstone, who later became well-known for his prayer guide, Operation World. Stephen and the others learned to build their lives around prayer, study and outreach. Thus mornings “were devoted to prayer and preparation, while each afternoon we began spending three hours out and about, visiting Christians to prepare for meetings, or visiting house to house. We would encourage converts in their new faith. By late afternoon…we would hold a simple open-air meeting to catch people’s attention on their way home from work. By seven we were down at the tent, preparing for the evening’s rally” (154). Johnstone sought to build up Stephen and other young Africans to take over the leadership of the evangelistic outreaches, something Stephen at first found incredibly daunting and difficult to contemplate taking on.

But he persevered and soon was leading missions all over southern Africa, besides getting married to Rachel, a Malawian, in 1969, with whom he has had five children. The most astonishing experience Stephen ever had in a mission came in 1975, back in Harare again, when he was exhausted after a whole day of preaching almost constantly.

He had just finished his last preaching assignment for the evening and made a halfhearted appeal for anyone wanting to come forward. “I unhooked the mike and was turning away from the platform, longing for a cool drink, when someone clutched at my trouser leg. I looked down. A little woman standing in front of the platform, looking up at me. I crouched down to have a better look at her. She was a bit of a mess. She was thin, looked ill and stank of alcohol. She was drunk. ‘I would like to pray with you,’ she said abruptly, staring at me in the most peculiar way” (191). Being exhausted, Stephen tried to fob her off to one of the female counselors, but finally prayed with her. But she kept hanging on to him, finally saying, “‘Do you know you are my son? … Back in Highfield,’ she said. ‘You and your brother John and sister Malesi. From what you said tonight, I know I was – am – your mother.’ Her words sunk in at last, and I felt the shock of it hit me like a physical force. The years peeled away and I relived the terror of that dreadful day. This small, shrivelled-up, ill lady was the glossy, round young woman that had abandoned my sister, my brother and me to probable death twenty years ago” (192-193).

Stephen struggled mightily to forgive his mother, but with the Lord’s help was finally able to do so. Amazingly, she grew in her Christian faith and enrolled in the same Bible school as Stephen had gone through and then joined the Dorothea Mission and became an evangelist herself! Stephen then tracked down his father in Malawi in 1986 and shortly thereafter led him to the Lord. He lived with Stephen and Rachel for some years and died at the ripe old age of 104.

Stephen was invited in 1978 to start up a new Dorothea team in Malawi and then in 1982 joined African Enterprise (AE), an international ministry focused on evangelising the major cities of Africa with teams in ten countries across the continent. Just at this time, he was given a scripture that portended his future.

Isaiah 55 reads: “I will send you to the nations that you do not know.”

New horizons opened up for this former street kid, as he soon found himself preaching not only all around the African continent, including a crowd of 250,000 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in 1994, but all over the world – in North America, the UK, Ireland, Europe and Australasia. He even spent six months living and preaching all over New Zealand in 2004 in an effort to build up a solid base of prayer and financial support for AE there.

“Because I look at myself as a miracle of God’s grace,” Stephen says, “so I believe that the power of Jesus Christ to save sinners still exists. If he can change me, he can change anyone… Winning souls for Christ. It’s my calling. It’s my passion. It’s me”.

Stephen Lungu was the Team Leader for African Enterprise Malawi from 1982 – 2006. He then became CEO of African Enterprise International, taking over from the organisation’s founder, Michael Cassidy. Stephen Lungu was succeeded by Stephen Mbogo as CEO of AEI in 2012.

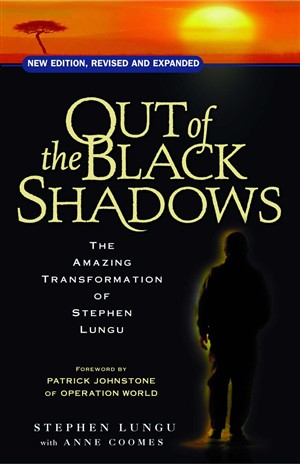

You can read Stephen’s full testimony in his book “Out of the Black Shadows” (page numbers referenced in this testimony).